Sexuality education is quietly ignored in Kailali schools

Kailali : School curriculum and textbooks in Nepal include sexuality education, but in practice students rarely receive the knowledge they need. Mainly in the rural places, students complain that lessons on sexuality remain confined to textbooks—hindered by social taboos, teacher discomfort and the absence of an open classroom environment.

Sarika (changed name), who is pursuing higher studies in a Dhangadhi-based educational institution in Kailali district, recalls studying ‘health education’ since grade six, yet understanding little about sexuality. “As soon as the teacher mentioned sex education, the classroom would turn awkward—boys giggled, girls looked away in shame,” she says. Despite her curiosity, she never felt comfortable asking questions.

Having completed her earlier schooling in Doti, Sarika says she never saw a teacher explain diagrams of male and female reproductive organs printed in the textbook. “They (teachers) just skipped the chapter. We didn’t even know what questions to ask back then,” she said.

Sarika’s first menstruation at the age of 14 brought confusion and isolation. “I had no idea what was happening. I had to stay away from home for 10 days once my sister found out,” she said. She now realised that she was left in trouble due to lack of effective sex education.

Sarika’s experience echoes that of Priya, another school student in Dhangadhi. She says that sexuality is either ignored or ridiculed at school. “It’s a serious topic linked to our lives, yet it’s treated as a joke in classrooms,” she laments. Priya, who is part of a child club, learned more through NGO workshops than school lessons.

A male student at Sharada Secondary School in Dhangadhi, also noted the gap between curriculum and classroom practice. “Sexuality education is in the textbook, not in our learning,” he said. Another 15-year-old boy at Durga Lakshmi Model Secondary School in Attariya said he relies on the internet to understand puberty and body changes. “Sometimes Google leads me to inappropriate sites,” he confesses.

It shows that sexuality education is not effective in classrooms. Most of the students complain that sex education has been completely ignored at schools.

Ganga Awasthi, a health teacher of Panchodaya School in Dhangadhi admits the curriculum lacks depth. “It just defines sexual and gender minorities but says nothing about their problems or lived experiences. We have to search on our own to teach comprehensively,” she shares her difficulties. She also argues that only one lesson in the curriculum addresses sexuality, far from sufficient for students to grasp complex concepts. She, however, says that even when teachers attempt to teach, students often become disruptive or embarrassed. “No matter how much we try, they don’t pay attention,” she added. The health teachers often complain that they lack both teacher training and content depth.

Some local governments have tried integrating sexuality education into their own curricula. Godavari Municipality in Kailali is preparing to launch a local curriculum titled Hamro Godavari, which includes basic concepts like good and bad touch. Education Officer Prayag Raj Joshi acknowledged the limitations but says it’s a step forward. “Though we couldn’t include much, we’ve made a beginning,” he said. Dhangadhi Sub-Metropolitan City has also added a unit on sexuality in its local curriculum Hamro Dhangadhi, but has not yet formulated a dedicated policy or programme.

The national school curriculum does not offer a separate comprehensive sexuality education course. Some components are integrated into courses like “Hamro Serophero” in grades 1–3, menstruation in grades 4–5, and basic sexuality education in grades 6–8 under compulsory health and physical education. In grades 9 to 12, health was once a compulsory subject but is now optional, meaning students can easily miss vital knowledge.

There’s no nationwide study yet on the effectiveness of sexuality education in the country. According to the 2021 census, 20.15 percent of the population—about 5.8 million people—are between ages 10 and 19. Dr Khagendra Raj Bhatta, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Seti Provincial Hospital in Dhangadhi, emphasises the urgency of sexuality education for the 10-19 age group. “Lack of knowledge leads to early marriage, unsafe sex, teenage pregnancies and unsafe abortions,” he warns.

A 2023 study by Human Rights Watch and World Vision International Nepal found that 37 percent of girls in Nepal marry before 18, and 10 percent before 15. Government data from 2023 shows that 14 percent of girls aged 15–19 are either mothers or pregnant despite the legal age for marriage being 20 for both male and female.

A study initiated by UNESCO in 2008-9 shows that sexuality education in schools reduces risky behaviour. It shows that sexuality education delayed sexual relations, reduced the number of sexual partners and increased contraceptive use.

Experts underscore the need for effective sexuality education at school level by enriching curriculum, managing human resources and providing training to the teachers.

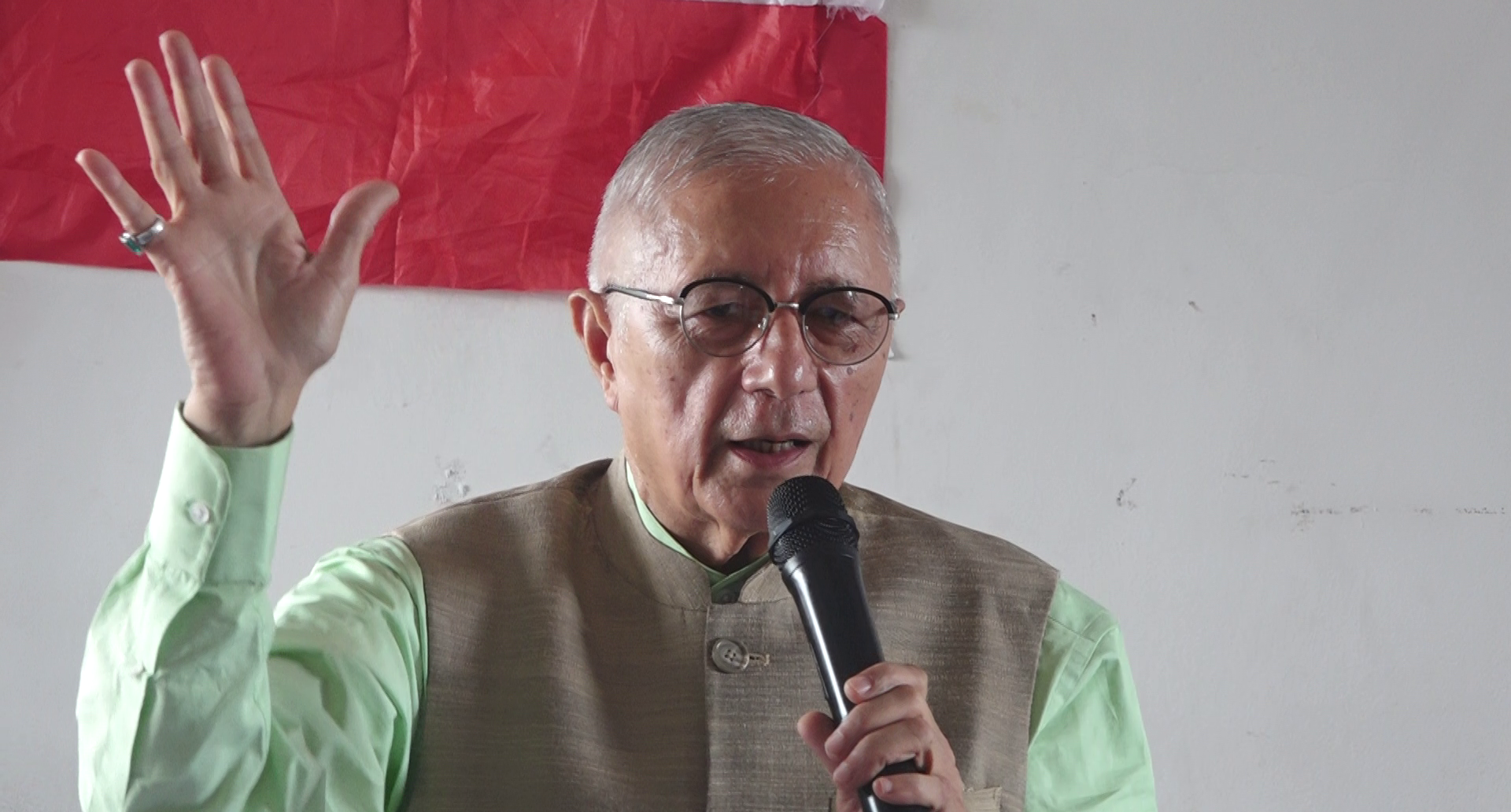

Assistant professor Sharmila Pokharel at Tribhuvan University, who is pursuing a PhD on sexuality education, believes the main problem is not content, but a lack of trained and qualified teachers. “Teachers need proper knowledge and confidence to teach this topic. Right now, it's often just the social or health teacher with no training,” she said.

तपाईको प्रतिक्रिया